Nudging with privacy

How to measure, ask and coach someone without knowing who they are.

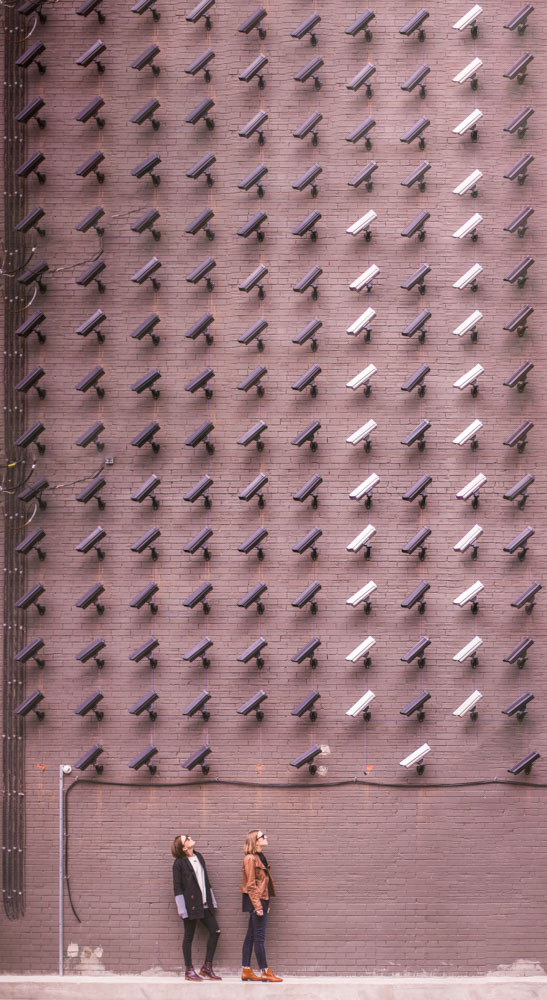

During this decade, the importance of one’s right to privacy has taken the centre stage. Face-recognition and machine-learning continue to develop, social media and data leaks made headlines and the implementation of regulations such as GDPR made companies feel like they can run, but never hide. How is MeBeSafe faring?

Researchers are often trusted with sensitive personal data which is highly important to anonymize. MeBeSafe is no exception. The nudges and measures address the behaviour of individuals, so it is no kidding, Sherlock that data derived from individuals is needed for us to investigate further.

In Gothenburg, Sweden, the Cyclist nudge – aiming to slow cyclists down when approaching statistically dangerous bike-car intersections, which was developed by Chalmers University – is currently being analysed from a quantitative perspective in order to indicate the effectiveness over time. This requires huge amounts of data which is collected from locations where the nudge is installed. In order to discern a change in the cyclist’s speed, it is necessary to know the speed from several moments before the nudge until the time the cyclists interact with it.

This could be done by video analysis, which means that the cyclists would need to be recorded. From a privacy perspective, that would also mean that each and every one of the cyclists would want to be asked beforehand so they can give their consent or not. That is of course not possible, but MeBeSafe manages to solve this anyway for the benefit of everyone involved. Instead of using image processing technology that relies on human interaction, Chalmers is using a system that processes motion activity to datapoints immediately, and it does this offline and at-location. Consequently, the data collected and transferred to MeBeSafe is not images of people, but merely the datapoints of each moving object and the respective speed-trajectory.

“If we had collected video material, it would have required a lot of paperwork! But as data is anonymized directly, we can begin collecting data both very rapidly and without infringing on anyone’s privacy.” Pontus Wallgren, researcher at Chalmers University, states.

This way it’s possible to collect large sets of data, which you can use to deduce or indicate whether or not something is working. However, to get a deeper understanding of the results and be able to change the desired outcome, you need to know why and how something works. Hence, you have to ask the individuals you’ve measured, but how do you contact them if you don’t know who passed by the nudge?

Since a nudge normally is designed to not require an active thinking process, you wouldn’t want to attract their attention in proximity to the nudge. It could possibly skew their normal behaviour, and that would be counter-intuitive for the research! So how can they share their thoughts and reasoning?

In the city of Eindhoven, the Netherlands, this matter was solved for the InfraDriver Nudge, a measure led by ika of RWTH Aachen University – aiming to slow down individual car drivers where appropriate – by cleverly thinking several steps ahead. Milou van Mierlo from Heijmans explains:

“We conducted a resident survey with a good recruitment strategy I may say. When we selected a road exit to install our nudge, we considered who would actually take that specific exit. We selected an exit so that if you come from the north, the drivers would most likely be residents of three specific neighbourhoods. We’re now quite certain that everyone who lives in these neighbourhoods and drive the car is likely to take that exit quite often.”

This means that the choice of location for the nudge instalment, can facilitate how effectively you collect feedback from a specific group of people. Naturally, it was one of several factors in the selection process; the main factor being the road exit showed potentially dangerous traffic situations. For example, drivers being surprised by the narrow curvature of the exit. Then again, factoring in how to collect user feedback has made it easier to come in contact with people who have experienced the nudge.

“That’s the benefit of the location we chose. Knowing this, we distributed a resident survey via Eindhoven citizen panels, with which the city can reach people based on the area they live. Additionally, we knew that neighbourhoods have a committee, so I visited one meeting of every committee and explained a little bit of the project and distributed the anonymous survey via them.” Milou van Mierlo asserts.

It is obvious that privacy is important when assessing how a solution works, but can privacy on its own affect how well the solution works? The measure in MeBeSafe that puts privacy at its core is the coaching app DriveMate by Shell, aimed at supporting truck drivers. The app collects data about driving style, acceleration and braking, but it is only shared with each respective truck driver in order for them to know what they can improve. The researchers can’t determine who is who on an individual basis. This is the case not only out of belief for someone’s right to stay anonymous, but because the coaching app probably wouldn’t work that well otherwise, as expressed by Saskia de Craen from Shell:

“There are countless apps for measuring driving behaviour. However, most of them focus heavily on someone else monitoring you. Drivers don’t like that, and even managers don’t really like that, because they have to talk to a driver not performing so well then, and those are of course not the easiest conversations. Based on our scientific research, we have concluded that coaching might be more effective if it is up to the drivers themselves if they want to share their personal data with anyone else. We call this ‘Empowering the driver’.”

It is significant to know, in the context of privacy, that the coaching app is supported by so-called offline coaching; face-to-face between peers. Only if the driver choses to take part, they will eventually share something with their peer, but it is still up to them to decide if they want to share and what they want to share.

It’s all about creating a familiar and protected environment. To allow the drivers to decide whether they share their private data or not is very important in creating that environment, in much the same way that people during everyday conversations share what they are comfortable with based on who they are talking to during a specific circumstance.

You may however ponder if this anonymization in some way could be harming research if we as researchers can’t tell who’s doing what? The short answer is that it depends on the end goal. Knowing who is doing what is probably not the end goal. It is however a common means to get to some other end goal, such as better performance in one or several aspects.

The end goal for the coaching app is to have the truck drivers ride more safely. It is not important to know which individual is driving how. Instead it is important to ask the question what would empower all of these drivers and increase their likelihood to become even better drivers. Instead of manager monitoring, the app answers with self-reflection, peer-to-peer coaching and high user-privacy. This is the novel concept of the coaching app.

Amidst the rising concern for privacy-rights, is the coaching app re-introducing an essential idea of how people prefer to be treated? That is yet to be determined, but so far, the reactions from truck drivers are very positive and their commitment has exceeded MeBeSafe’s expectations.

In the future decade, we can expect privacy to take on an even more central role. And with that we can expect the demand for personal privacy – or simply people wanting to be approached based on consent and fairness – to become an even higher priority. How will future services and products adapt? What kind of research needs to be done in the scientific world? How will it be conducted? Would it even be embraced in practice?

We don’t know. What we do know however, is that whoever the research may involve, that it is possible to measure cyclists, ask car drivers and coach truck drivers without knowing who they are in person. We don’t know, and in order to make traffic safer, we don’t have to.