Will a good nudge affect workload?

A nudge could reduce speed in two main ways. Either because it triggers an automatic response to reduce speed, or because it takes up so much attention that it makes it impossible to keep the current speed. How do we make sure that it is the former?

Speed is sometimes very important. When a car leaves the motorway on a curved exit, then high speed could mean sliding off into the bush. When a car and bike are about to cross each other’s way in an intersection with blocked view, high speed could mean failing to spot one another in time. MeBeSafe is trying to solve these problems by nudging techniques.

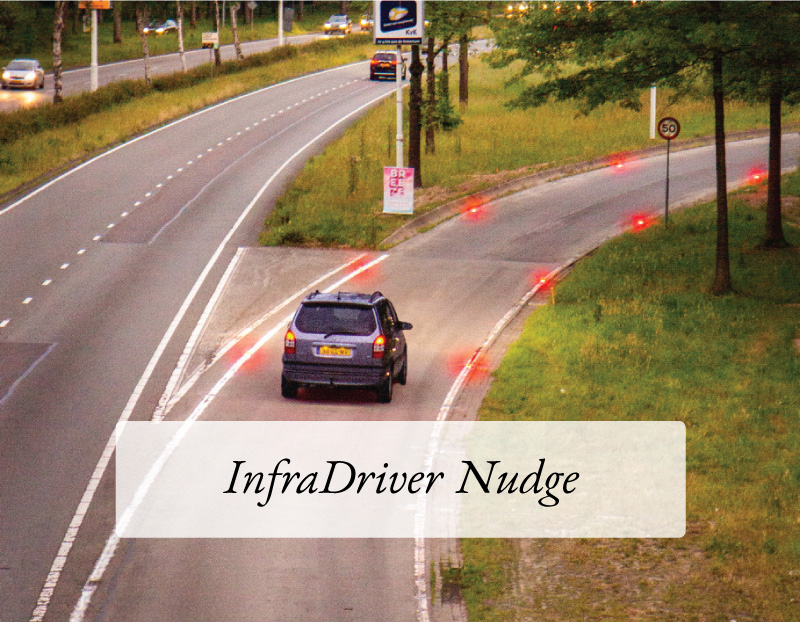

A contrivance called the InfraDriver nudge will help drivers to reduce their speed at motorway exits by using lights that move. Another one called the Cyclist Nudge will help cyclists adapt their speed before intersections, and the third one called the In-Vehicle nudge targets drivers in the same scenario.

It is tempting to say that the nudges are a success if they reduce speed. But that’s not the whole truth. If the nudge takes too much of the drivers’ attention, they might still happen to crash into something. It is therefore of utmost importance to evaluate the nudge in terms of attention and workload.

Gothenburg; on the barren shores of West Sweden. A cyclist runs down the lane. She has a camera on her head finding out in which direction she looks, and another one on her bike to capture her speed and trajectory. She is part of Chalmers’ first major nudge study, made by Pontus Wallgren and Victor Bergh Alvergren. This early test served to measure the effectiveness of various nudges in terms of speed as well as attention.

And the results were interesting indeed. Two nudges were found equally effective in reducing speed. The first one worked by seemingly narrowing down the lane due to the sidestripes moving gradually inwards. The second nudge had an array of stripes running right across the road, getting closer and closer together. In terms of speed, both made the cyclists slow down a large amount. But there was one major difference.

The head camera measured how much the drivers turned their heads around and looked towards the left and right before the intersection. More or less, how attentive they were to the surrounding traffic. The narrowing nudge seemed to make them look much less to the left and right, while the stripes found no such effects. This exciting discovery made selection of a nudge for the field trials very easy.

“The narrow nudge was not really a feasible alternative. Although appreciated by cyclists and effective in reducing speed, it seems that it only reduced speed because it demanded attention. And the pattern was the same even if the cyclists were not aware that they had seen the nudge.” Pontus Wallgren proclaims.

The very same reasoning goes for the Infra- Driver nudge, but here attention was treated in a rather polar way. Drivers were recruited to drive around in a driving simulator at ika where they eventually would encounter the nudge. But they were not only to focus on driving – no, they were given another task that they should do at the same time.

They were for example told to look at an in-vehicle screen and try to find the largest circles among other peers. All the time, their attention was identified by measuring how well they succeded. So their point of attention could be known all along the trip.

Naturally, drivers put a lot of effort into their secondary task when driving at a normal road. But when the nudge appeared and the lights turned on – their attention seemed in many cases to be moving away from a secondary task. The nudge then clearly seemed to redirect their attention to the nudge and to the road. This remarkable finding indicates that when a driver is doing something else, the lights could make them more aware that something is going on around them.

“This is interesting, but the most interesting thing is not that the nudge works – but how it works” Anna-Lena Köhler from the ika states. “It has an effect on speed, but it is rather small. Some people might misinterpret that to mean that the nudge is not working. But that is not the case. Since it makes people more aware of the situation, it is instead highly likely that it really works.”

So while the design for the cyclist nudge was chosen because it did not take any attention away, and allowed cyclists to look around for others who might cross the intersection – the InfraDriver nudge was found good because it did take some attention. It showed you how you should drive, but also directed attention away from other secondary tasks to the real world. And in a curved exit, with no crossing traffic to be spotted, that is of course the main focus.

So a good nudge could very well take some attention and workload – if the situation demands it. And in terms of attention, the two nudges really seem to serve their purpose. One takes no attention, and the other directs it. Right towards a safer future.